Silvia Amancei & Bogdan Armanu, Sneha Khanwalkar

Cola & the Chips

essay by Maximilian Lehner

A delivery driver walks into a restaurant. Knowing that some places have separate entrances for the pick-up of ordered food, this is not going to turn into a light joke. Even if told by Slavoj Žižek,[1] it would probably turn into a rant on the ingenious use of the idea of ‘freedom’ in the large platforms of today’s gig economy.

But we see none of that in s.a.b.a.’s music clip Cola and the Chips. There is only a shot of one driver with the cubic backpack which became the key piece for this business model. Going through a dark night with wet streets sums up the everyday annoyances of the underpaid drivers, when someone just wants to get their fries and a coke at home, maybe after an annoying day of working for another terrible company – maybe even for Coca Cola, at least they own or partner with many of the global food delivery companies.

Imagine a conversation on the moral contradictions in ordering food home. The conflict might involve someone who endorses that the workers’ rights are being violated, people live in terrible conditions and accept bad working conditions, and someone who holds the belief that it is better to have jobs for everyone, no matter what kind of job. In a small qualitative study on the UK, the drivers interviewed – all male –, mostly had Pakistani or Indian origins, many came for their studies and illegally pursued the job through renting an account with one of the platforms.[2] Still, some other researchers – this time for Australia – might say: “In sum, these jobs are labelled ‘poor-quality’. But this description doesn’t seem to fully capture the experiences of the gig workers we spoke to. The young men […] seemed cheerful and happy. As foreign students, they were keen to improve their English, make friends, and earn enough to get by.”[3] Yet another person in the imagined conversation would just think about the convenience of getting food delivered at home, because they are suffering from their own jobs, are exhausted, and regularly use this possibility – despite knowing about the bad working conditions.

The doorbell rings and food arrives – as impersonal as this sentence suggests. None of the beforementioned protagonists addresses the topic or even speaks to the delivery driver directly. It’s a confusing world out there. The exchange that happens is a clearly economic one, even though this part is outsourced in an app and no cash or transfer happens at the door. No humane addition is needed here. I mean, it’s only a dark and rainy night out there.

Interestingly, these personal factors are rarely taken into account, even though they are present in union(-izing) demands or discussions about the bad labor conditions in these fields. Gig economy is rather a playground of optimizing models for logistics, algorithms, and human resource management. Neither at the doorstep, nor in the further development of the platforms, the most obvious problems of this work can be addressed appropriately. This is just more comfortable. This comfort is needed because of self-exploitation in a system. The riders also exploit themselves in believing in the promise of freedom. As Žižek points out in an interview, they are only competing with their co-workers, not against the companies.[4] The freedom of choosing when to work or not, being on the app or not, as well as the low threshold to enter this field without prior knowledge gives those who join actual agency – or at least it appears better at first sight in comparison to other terrible job opportunities.

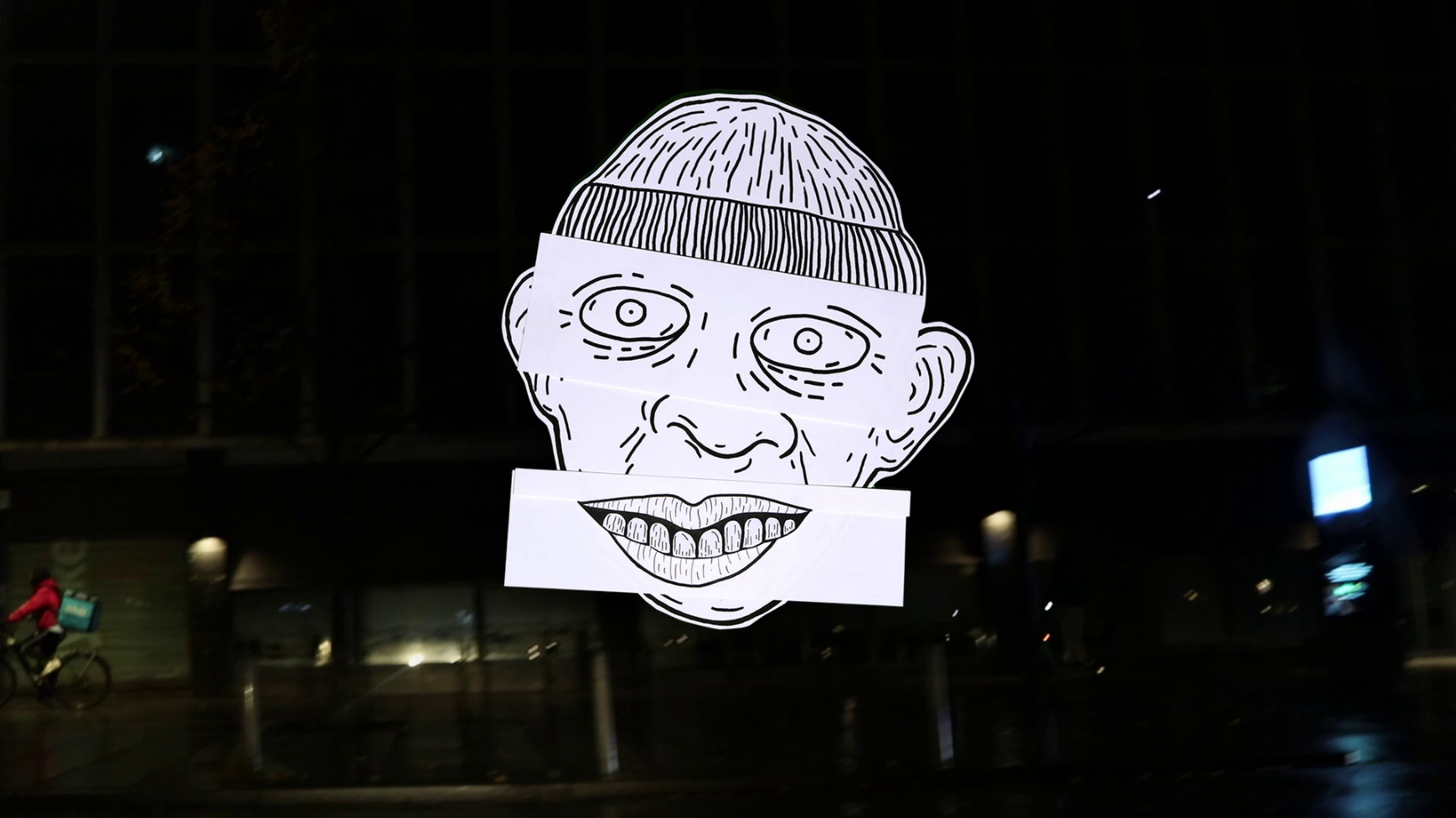

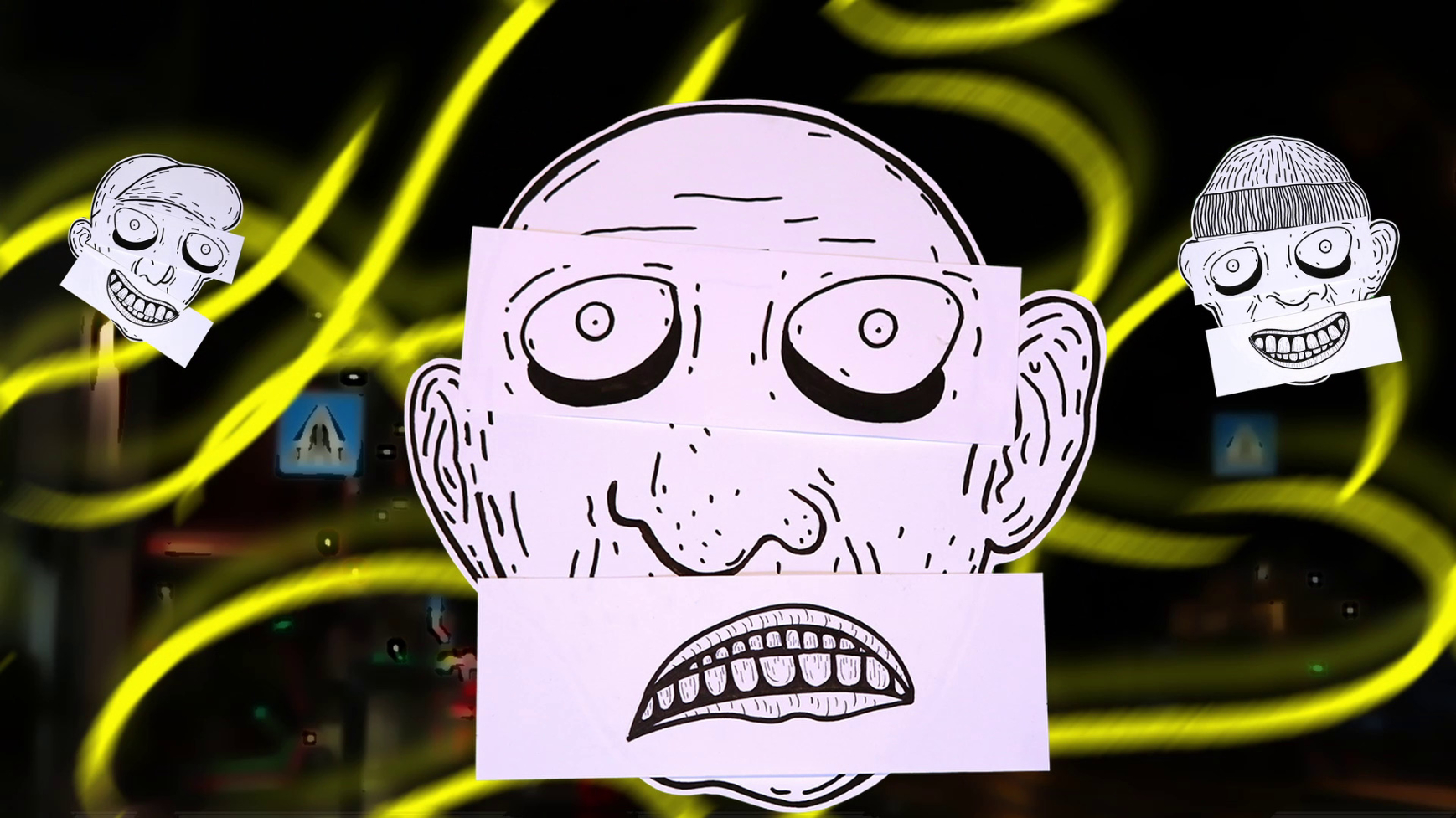

In the video, the drawings of the faces of the drivers are shaky, their expressions turning into the opposite from one second to another, just by inverting the eyes and lips. That might be the moment they saw Žižek’s interview in their social media feed – until at some point the eyes of the cut-out protagonists become one with the background, they’re just empty. But this emptiness is not only due to the dumb task of following the algorithm attaching rides to their bodies, it might even be empty stomachs (thinking of the interviews from the UK study, it is many delivery guys with multiple jobs to maintain their families). They might need to order food, too. No. But at least one of them rather bites the food that was ordered by someone else.[5] Understandable. It is also comfort. There might be a burger or some chips in the box he opened.

While already for quite some time having fries with coke would feel like pure guilt – a multinational company paired with greasy food, sugar, additives –, the process of ordering adds another layer to this dilemma. So, it has to be rendered invisible. Just make it not too easy to choose when you have everything available, like on-demand streaming where you are exhausted because you cannot decide, the things you want might cost extra, and when you found something bearable you already don’t want to see it anymore and are happy that you managed to get through the process of deciding. I always thought prosumerism sounds so 90s. But we get involved to make us think about how much we contributed and not consider the others at the restaurant and on the street.

Once upon a time, these forms of gig work were only imagined on the horizon of what might be possible in the future. Some might have still dreamed of the effects automatization impacting everyday life, and that full automation of production could have led towards enabling basic income, shifting the work force towards machines and the creative side to humans. Gig workers are yet another instance of the dystopian side this is turning towards, but in slow imperceptible steps: It cannot be that bad when the delivery person is smiling and telling you to enjoy your meal. You contributed, and you ordered, you did everything and the other just had to follow the machine’s instructions.

So, it is definitely not a gift, it is an exchange. This is also mirrored in the tips given, when people order who think of it as treating themselves with something special, they seem to give less. Those who could feel empathy, maybe don’t want to feel the guilt. But how to escape. Go on a delivery bike? But can we take a break and take a step back and look at the situation? Think of some French philosophy that would never contribute to this discussion –

Jean-Luc Nancy used the idea of the clinamen, the space in-between molecules to describe communities, and the individuals within. This inscribes into a tradition of thinking about alterity in intersubjectivity, the question of how we are actually able to understand and interpret others when we encounter them. How does someone make sense of the delivery driver at the doorstep? While Nancy’s (and other philosophers’) thoughts only help with the fundamental ontology of encountering the other as another human being with intentions, this detour does not help with understanding the impact of economic entanglement of the other. The problem is the overall participation in this economy that we might want to avoid. We want to bridge the difference, the clinamen. We desperately want to fill it with a tip, with pretending to understand, to tell friends how we know the delivery person and make ourselves seem like good people.

But there is no way of being good. This text is obviously written from the perspective of not being on the delivery bike, like most of the other texts criticizing the exploitation going on in businesses like food delivery. And despite sounding so terribly moralizing, it should be read in a light way like the video Cola and the Chips. I wrote in other instances about s.a.b.a.’s works and how they play with the inevitability of joining the large global platforms, even when you try to criticize the business models and philosophies behind them. Since most of us are somehow part of this – willingly or not –, it is easy to accept our weakness towards these large-scale industries and networks built around them. Many will respond that they refuse to join them, and I am happy if that resistance is actually possible for as many as there will be claiming this. But I rather turn to the negative thoughts of feeling guilt at the doorstep, deciding for comfort because one feels like having suffered all day from another job. Cola and the Chips does not leave us with any of these thoughts, we only come back to them if we had them before. The video can let the ‘clinamen’ exist, the thought that we will never bridge the differences in background and experience, and which we can also not fill this with guilt or empathy. And even though s.a.b.a. don’t make it so explicit in this video, again they participate in the spectacle of media attention to draw attention to something so intrinsically part of it, that in the end it might go unnoticed. They pull the drivers into a music video and leave the moral judgement open. The lyrics of Sneha’s song at times wail like a siren, alarming us to act. But we know – and I hate using this all-encompassing ‘we’ here, in spite of a better way to frame a circle of people who would agree with this. The beauty of this video is to accept the weakness in watching the footage and animations as a reference to the invisible and yet so present situation of gig workers, without the moral imperatives. Within a realm where people mostly agree on the criticism, there is no need for a text like this one, so I wrote it to say that this artwork probably will not change anything – as so many works before did not. But I am stuck with the thought of accepting one’s weakness, one’s moral deficiency, and still wanting to change things. Maybe this has to start with a music video, maybe from one’s lounge-y chair while the pizza delivery is coming and at a time when none of the interlocutors of that annoying discussion weigh in their arguments without being able to contribute to change and respect in their proximity. Just let them eat cola and chips!

Cultural project co-financed by the National Cultural Fund Administration.

[1] He is referenced because conversations with s.a.b.a. have always been infused with his theories. Otherwise, the quotes and references are more unsystematic online finds from reading too much on gig workers.

[2] See Promises_Perils_of_Gig-based_Work_A_comprehensive_study_of_food_delivery_workers_in_London

[3] See workers-the-pros-and-cons-of-delivering-food

[4] See https://www.instagram.com/reel/C0hAMP9i1cU/

[5] See zomato-delivery-boy-opens-food-pack-eats-seals